Andrew Wyeth | As A Theorist

Wyeth in a Word

evocative (adj)

bringing strong images, memories, or feelings to mind

In the recently released film, Blade Runner 2049, sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 neo-noir sci-fi film, a pivotal character with a compromised immune system, Dr. Ana Stelline, remains in a hi-tech bubble provided by her parents with everything she needs to be happy and productive in her life’s pursuits. Within the bubble she manipulates holograms based on her memories of life before her confinement and constructs the memories of other “replicants” to structure their personalities. In support of the validity of her work she states that “every memory has a piece of its artist; if you have authentic memories, you have real human responses.” (i) Herein lies the legacy of artist Andrew Wyeth’s evocative and widely received oeuvre.

Fully-Formed at Fifteen

I built my own stories, and that is what painting has been to me. you don’t have to paint tanks and guns to capture war. You should be able to paint it in a dead leaf falling from a tree in autumn.

-Andrew Wyeth, A Spoken Self-Portrait (ii)

Son and student of N.C. Wyeth, a renowned artist and illustrator, Andrew Newell Wyeth III was born in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania on July 12, 1917, the youngest of five siblings. Chadds Ford resides in a valley located twenty-five miles southwest of Philadelphia, fostering a farming community and nourished by the Brandywine River. N.C. Wyeth, with his wife, Carolyn, bought eighteen acres of land on a hillside south of the town in 1911 where he built a house and a studio—”This little corner of the world wherein I shall work out my destiny.” (iii) Little did he know that hill would be a formative subject in his son Andrew’s paintings. N.C. and Carolyn had five creative, productive, and independent children, all homeschooled under N.C.’s watchful eye with tutors. A sickly child, like Blade Runner’s Dr. Stelline, always dreaming, admiring, and reflecting, young Andrew was constantly drawing, sensitized to his surroundings and involved in gathering up his own impressions into his imaginary cosmos. “Andy was so attuned—but in such a fragile way that it could almost destroy him…he’s vulnerable to everything!” said one of his sisters. (iv) Upon his birth, his eldest sister looked down at him in his crib and declared he will become a musician or an artist.

Andrew, who felt misunderstood by others his age, knew early on that painting and drawing was his “only chance”, that evoking moods, emotions, and mutating reality with fantasy was the most exciting pursuit. He dove into a disciplined yet unorthodox artist’s education under his father’s principle: too much fact constrict fantasy; imagination feasts on the hidden. (v) By the age of fifteen, when he began lessons under his father, Andrew Wyeth was wholly formed into the famous artist he was to become, and maintains his childlike excitement for his surroundings throughout his career. By the age of twenty, Wyeth had his first exhibition, a one-man show of watercolors, at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. Every painting was sold, and his career’s destiny was as set as his father’s decision to buy family land in Chadds Ford.

Wyeth’s father had instilled a love of rural landscape, thrilling and romantic literature, alongside artistic tradition in young Andrew. What N.C. gave Andrew access to, Andrew’s imagination brought a unique voice. When it came to his choosing of subjects for his paintings, Andrew preferred to set a scene embellished by his imagination and simplified through memory, rather than draw his chosen perspective to photographic truth. In fact, he refused to work from photographs, unlike other contemporary artists. He preferred to revisit a place or study an object over and over, sometimes taking it hostage in his studio where he dreamed up its abstracted meanings and inherent memories. This period of marinating is accompanied with countless studies and pre-studies, in sketches, in painted form, of every tempera and dry-brush painting Wyeth has ever made. What he chooses to paint, he paints in immaculate, calculated detail down to the number of fruits on a tree or strips of clapboard on a barn house facade. In doing this, he aims to capture the essence of an object, a person, a place within a scene, not simply its re-presentation in a systematic painting technique: “Nothing I’ve ever done has scratched at the surface of what I want to do.” (vi)

Symbolic Not Bucolic: Two Landscapes of Wyeth and Realism as Symbolism

Maine to me is almost like going to the surface of the moon. I feel things are just hanging on the surface and that it’s all going to blow away. In Maine, everything seems to be dwindling with terrific speed. In Pennsylvania, there’s a substantial foundation underneath, of depths of dirt and earth. Up in Maine I feel it’s all dry bones and desiccated sinews. That’s actually the difference between the two places to me.

-Andrew Wyeth, A conversation with Thomas Hoving (vii)

Coinciding with an upbringing in Chadds Ford, the Wyeth family made a second home in Cushing, Maine where they vacationed year-round. Cushing is a coastal town—one overnight train ride’s distance from Chadds Ford—known for its unspoiled natural scenery, lobster fishing, and Colonial farmhouses. These two locations, and its locals, subject to Wyeth’s discerning eye and sensitive spirit, are considered the two fundamentally important environments of his life. (viii) Specifically, at each location, he found excitement and immersed himself in the farmhouses of two families: The Kuerners of Chadds Ford and the Olsons of Cushing. Wyeth brings to life in his subjects his deepest childhood memories and associations, driven by his excitement for drama in a scene created by the abrupt appearance of life by chance:

“Subject matter has always been of paramount importance to Wyeth, especially when it comes to him unexpectedly, or, as he likes to put it, “through the backdoor”: He may start a scene and then see something days or weeks later that will make him completely change the first impression and, of course, the picture. He thoroughly believes…that you never have to add life to a scene. If you quietly sit and wait long enough, patiently enough, life will come—sort of an accident in the right spot.” (ix)

In his work Wyeth brings his emotions to bear in conceiving and creating a painting. A dreamlike realism representing free, often dramatic, symbolic associations in his work is what guided his sustained six-decade career. Guided by underlying emotional and spiritual impulses, Wyeth’s independent character drove him to paint only for himself, an inner self-confidence instilled in him by his father, with little care of how his work is received. In fact, Wyeth has complained about his work gaining too much reception and praise. The strength in his symbolic associations provide a mystery and incongruity to a scene by chance, an idea that keeps building in his mind. In his 1979 tempera painting, Night Sleeper (figure 1), Wyeth depicts his dog, Nel, with a sleepy, dazed expression on her face sitting in front of two windows facing a mill situated in the landscape, glowing with moonlight. The feeling of the atmosphere in the night, mysterious “moods of light” (x) whether depicting the actual moonlight or not, makes the painting feel somewhere between a wakefulness and a dream-like reality. He studied the moonlight hitting the mill by painting it outside, plein air. Wyeth recalled the overnight train to Maine that he rode as a child with his family, which he associated with the patch of moonlight against the earth. The reading of the painting transforms scenes and geography, we see a sleeping dog in transit. The dog now rests against a bag of unknown treasures, a traveler or a runaway’s companion. The two windows, though responding to the same moonlight, seem to be depicting two different landscapes—the starting point and the destination. About Night Sleeper, Wyeth says, “I didn’t want a half thought; I wanted a whole one. People think it’s half Pennsylvania, half Maine. It’s actually Woodward farm in Chadds Ford, based on actuality but freed from any beginnings or ends.” (xi) Left to chance, Wyeth simply woke up one night and walked downstairs to find his dog with a strange expression on her face.

Figure 1. Night Sleeper, Andrew Wyeth, 1979 (Brandywine River Museum Online) Tempera on panel, 47 x 72 inches

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Wyeth

Seeing the landscape up close, discovering what ‘lurks close down at the surface’, symbolizes the nature and intimacy of the Pennsylvania Landscape for Wyeth. His works are a balancing act of a reliance upon dreamlike, personal association and obsessive, faithful observation of a detailed subject. Wyeth found value in observing nature from inches away to preserve that which is otherwise underappreciated or compensated for with application of color in a painting; a skill, without which, he says he could not have done his famous 1948 landscape portrait, Christina’s World, which hangs at the MoMA to this day. Walking was considered by Wyeth a primary means of inspiration for his landscape scenes. In Wyeth’s 1951 self-portrait, Trodden Weed (figure 2), he views himself, nature, and his close brush with death from inches off the ground, while walking the country around Chadds Ford after a dangerous lung operation. Wyeth says about his self-portrait, “I had to watch my feet because I was so unsteady. And I suddenly got the idea that we all stupidly crush things underfoot and ruin them—without thinking. That blackline [weed getting crushed] is not merely a compositional device—it’s the presence of death.” (xii) During his surgery his heart stopped once and he saw death come and recede in the form of Albrecht Durer, whose detailed paintings Wyeth studied often. The painting is death, dangerous and looming, melancholy ochre hues punctuated by black lines and vernal wisps.

Figure 2, Trodden Weed, Andrew Wyeth, 1951 (Flickr Online) Tempera on panel, 20 x 18 1/4 inches

Private Collection

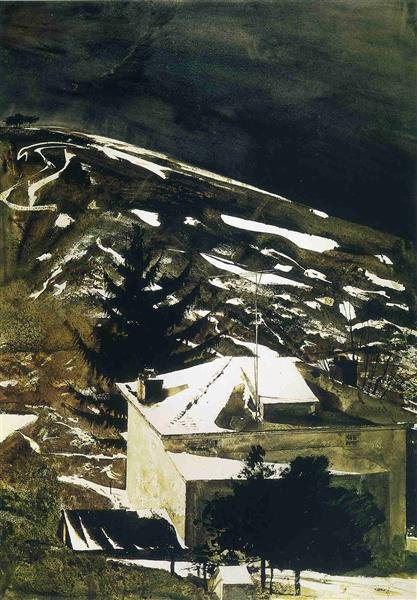

“Carried away to the point where his fascination with the details began to impinge upon art, the artist was able to take hold of himself, calm down, and create something deeper and more universal than a mere inventory of intriguing forms. He wanted to paint ‘a true portrait…not a picturesque portrait’.” (xiii) In his watercolors, Wyeth, encouraged by his father, went ‘out of his mind’. In Wolf Moon (1975) (figure 3), Wyeth, in a still image, depicts motion, sound, light, the feeling of the presence of a human in their home, while the viewer is elevated in the air, outside the house, above the scene. From outside the landscape reads as wintry, primitive, wild. The white snow and ice in the scene is bare, unpainted paper, and the moonlight brightens the snow in a reflective glow as the eyes move up the canvas across the frenetic movement of the landscape, punctuated by patches of snow. Between the patches is that which was left unpainted—or is it the frothing water on the shores of Cushing, Maine? The black sky, the relentless horizon of the ocean? The memory association: Anna Kuerner at her Chadds Ford farmhouse doing her house chores, going up and down the stairs in her home:

I’ve watched the Kuerners in the evening from the top of the hill, seeing the lights go on in the house. And I know Karl’s going to bed, going up the stairs, his shadow going by a window. You see lights going off and you can practically see the whole—what he’s thinking, what he’s doing. I love small windows, looking in or out, the glimpse of a landscape stirs your imagination if you don’t see too much. (xiv)

This is a truer portrait of landscape and landowner than most picturesque landscape scenes. As Vittoria di Palma states in her essay, “Is Landscape Painting?”, the picturesque invites the viewer to move beyond their passive role as observer of scenery and act as “an active force in its constitution as landscape.”(xv) In the case of Wolf Moon, the landscape is well-constituted, untamed, the narrative resonant. The reader need only to unravel the confusion that Wyeth revels in creating. Andrew Wyeth is not creating bucolic landscape paintings. He presents a depiction of nature—physical landscape of the human involvement in the landscape scene, making their mark upon their surroundings—realism as an ‘accurate evocation of a dream.’ (xvi) Wyeth has his own concept of the picturesque composition in landscape painting: “So much can be said by so little, the less I put in a picture the better. It’s what you bring to an object that makes it.” (xvii) It takes an artist like Wyeth to first read the land in this way and then sit and maintain the vision as it is rendered by his painted action. He completed Wolf Moon in thirty minutes.

Figure 3. Wolf Moon, Andrew Wyeth, 1975 (ArtStack Online) Watercolor, 40 1/8 x 29 inches

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Wyeth

A depiction of nature is ‘an accurate evocation of a dream… So much can be said by so little; the less I put in a picture the better. It’s what you bring to an object that makes it.”

In Wyeth’s 1993 painting, Whale Rib (figure 4), he depicts a portrait of a place, Bennes Island off the coast of Maine, as a state of physical reality and a state of mind—’a place in which things are constantly in danger of being blown off the face of the earth…the painting is almost a scientific tract, an official inventory of the flora and fauna that can exist only on this specific and single tiny island…Whale Rib is broad and universal, specific in almost a picky way and emotionally powerful, no less than a nature walk and the reminder of the inevitable end of all things human, natural, even cosmic.’(xviii) Wyeth painted this work while lying on his side during a storm. The large whale bone, dwarfing the flora and fauna on the shore—and Wyeth himself—depicting what the vast depths of the ocean can hold within itself and spit up onto land. A present-day reading of this painting cannot ignore the environmental implications of its subject, the inevitable end of man as we continue to live unguarded, deluded by the Age of the Anthropocene, desensitized to the endless ocean depths that can swallow us whole. The whale rib and rumbling waves are only the first warning of a storm to come, a war waged between land and sea. And yet, according to Wyeth, perhaps this is a tension that has always existed, “there’s a strange feeling that, yes, you’re seeing a thing that’s happening momentarily, but it’s almost a symbol of what’s always happened in Maine,” (xix)

Figure 4. Whale Rib, Andrew Wyeth, 1993 (Pinterest Online) Watercolor, 275/8 x 29 1/2" inches

Private collection

Love & Hate: Wyeth’s Confusing Nature

There’s enough here for you to find in it your own voice.

-Wyeth to Karl Kuerner’s grandson upon being asked if he may also pain tin Chadds Ford (xx)

What drove Wyeth to paint the ‘facts of things’ was a self-motivated desire to express himself—a portrait in a landscape, an alchemy of memories into a reality. art critic, Robert Hughes, said, “If the most famous artist in America is Andrew Wyeth,…[it is] because his work suggests a frugal, bare-bones rectitude, glazed by nostalgia but incarnated in real objects, which millions of people look back upon as the lost marrow of American history.” (xxi) In Wyeth’s unique view, nothing from the past is lost. His wife, Betsy, said of him:

The past and present are constantly swirling in and out, back and forth. Andy talks about intangible speech, the sound of a voice that’s not there anymore. The sense of history that’s gone before. Wars that have been waged. Births. Death. Violence. Storms. It’s almost as though he senses the ghostlike residue left. He told me once that the Gettysburg Address is still floating around in the air and will be recalled sometime. (xxii)

Wyeth’s view of the persistent relevance of memory stems from his awe of nature: the sublime, the eerie, the dramatic. He eschews artists who feel their depictions of nature are more important than nature itself: “if you know nature, you know how infinitesimal our abilities are.” (xxiii) He is humble before that which is much greater than himself and yet it is that which is also part of himself. Aspects of nature are reminiscent in Wyeth’s character: self-sufficiency, perseverance, tenderness toward all living beings, the people who live unappreciated, ‘reduced by life’, often featured as subjects in his paintings: crippled Christina Olson, ethnically diverse individuals, the elderly, the doe-like young, lower-class workers, depictions of melancholy, understated winter seasons and the hope of spring. However, he features these people because he is oblivious to how the rest of the world posits these individuals; Wyeth only sees the way he sees. He sees dignity, purpose, beauty, and ultimately, his friends:

“I think one’s art goes as far and as deep as one’s love goes. I see no reason for painting but that. If I have anything to offer, it is my emotional contact with the place where I live and the people I do.”

However, Wyeth isn’t Wyeth without contradiction and confusion: “love is not nearly as useful as hate.” In this ricochet of wild emotion and tender humility, Wyeth is drawn to the simplistic limitations of realism: winter’s melancholy whiteness and the complexity of emotion, “I begin with emotion and am excited to the point where it affects my stomach. that’s where I’m odd to paint the way I do, these immaculate pictures, closely done. You’d think you’d find a very calm mathematician.” (xxiv)

The conflicting nature of love and hate is what Wyeth felt toward his devoted father, N.C., who died unexpectedly in 1945, when his car stalled on train tracks in Chadds ford near their family home. N.C.’s nephew was also in the car. This event, in Andrew Wyeth’s view, was the loss of the most important person in his life. It took him out of being an “artist”, shattered his very foundation, into “actually facing life…it gave me a reason to paint. I wanted to get down to the real substance of life itself—a terrific urge to prove that what he had started in me was not in vain. I had to have something to pound on…My God, get to work and really do something.” (xxv)

Notes

i Blade Runner 2049. Dir. Denis Villeneuve. Perf. Ryan Gosling, Harrison Ford. Alcon Entertainment, LLC, Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., and Columbia Tristar Marketing Group, Inc, 2017. Amazon Prime. Web. 3 February 2017

ii Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait in conjunction with exhibit Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In, National Gallery of Art, Washington 2014 (Distributed Art Publishers, Inc, New York, 2013), 29.

iii Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc, 1996), 29.

iv Ibid., 30.

v Ibid., 52.

vi Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 103.

vii Thomas Hoving, Two Worlds of Andrew Wyeth: A Conversation with Andrew Wyeth (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978), 3.

viii Ibid., 4.

ix Thomas Hoving with commentaries by Andrew Wyeth, as told to Thomas Hoving, Andrew Wyeth: Autobiography (Boston, A Bulfinch Press Book: Little, Brown, and Company in association with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1995), 11.

x Ibid.,14.

xi Ibid., 118.

xii Ibid., 33.

xiii Ibid., 13.

xiv Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 92.

xv Vittoria di Palma, Is Landscape Painting? Ed. Doherty and Walheim. Is Landscape…?: Essays on the Identity of Landscape (New York: Routledge, 2015), 59.

xvi Thomas Hoving, Andrew Wyeth: Autobiography, 12.

xvii Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 51.

xviii Ibid., 14.

xix Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 17.

xx Andy Friedman, A Journey in Pictures for Andrew on his Centennial Birthday, The New Yorker (July 12, 2017) Accessed: February 5, 2018.

xxi Robert Hughes, The Rise of Andy Warhol, The New York review of books (February 18, 1982), 6-10.

xxii Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 79.

xxiii Ibid., 53.

xxiv Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, 14.

xxv Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Spoken Self Portrait, 99.